The process of European integration, culminating in the formation of the European Union (EU), aimed to foster unity, peace, and economic cooperation among European countries in the aftermath of the Second World War. While many European states embraced this vision wholeheartedly, Britain’s relationship with European integration was marked by ambivalence, scepticism, and periodic opposition. This has led to the widespread characterization of Britain as a “reluctant European”—a nation that engaged with Europe pragmatically rather than idealistically, prioritizing national interest over a collective European identity. Britain’s participation in the European integration project was driven by necessity rather than ideological commitment, and its path through the EU—from initial refusal to join, later accession, opt-outs, to the eventual Brexit referendum of 2016—exemplifies its hesitance.

1. Post-War Context and Britain’s Initial Distance

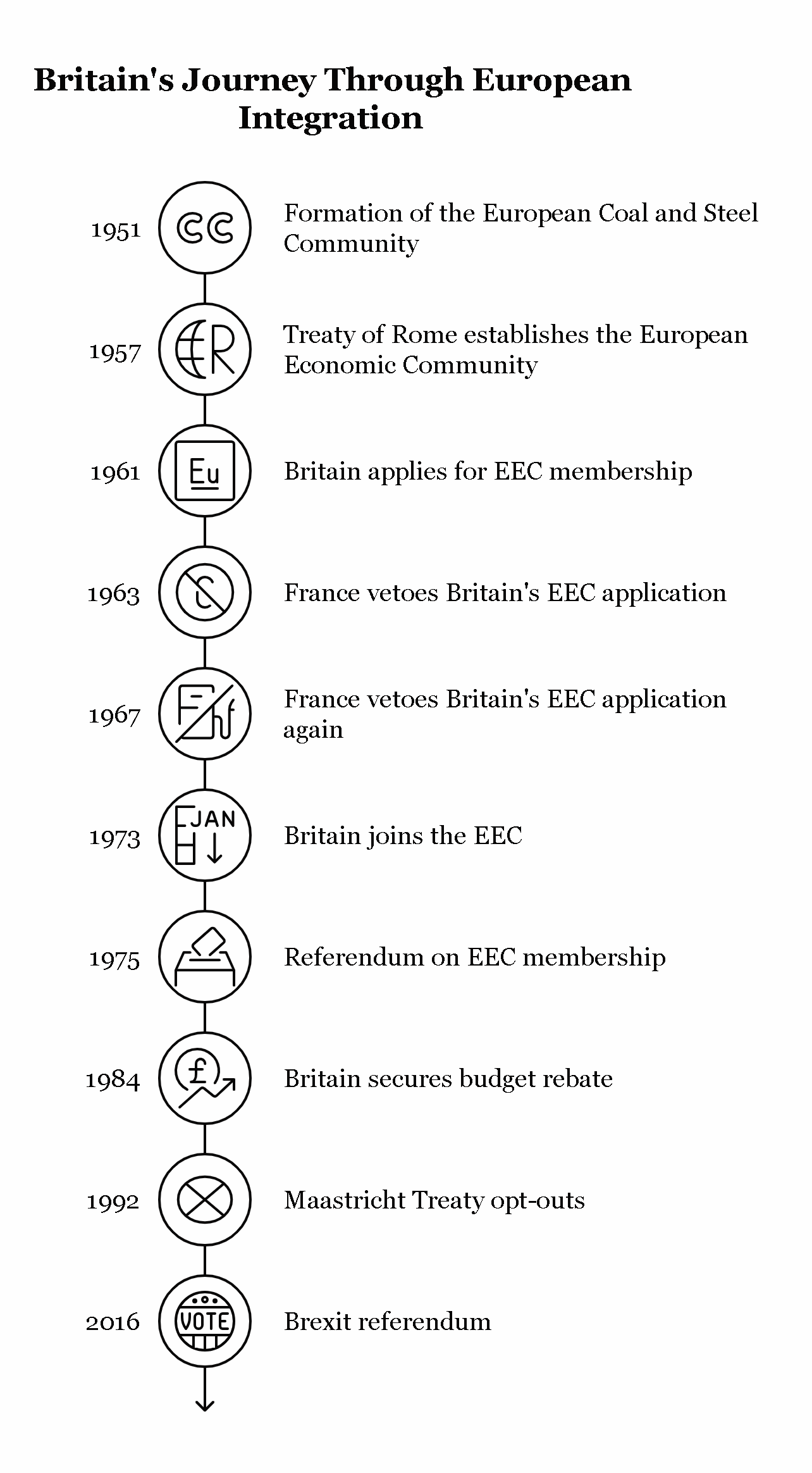

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Western Europe began moving toward integration through initiatives such as the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951 and the Treaty of Rome in 1957 which established the European Economic Community (EEC). These initiatives were driven by a vision of lasting peace through economic interdependence, especially between historic rivals France and Germany.

Britain, however, chose to remain outside these foundational developments. Several factors contributed to this:

- Imperial legacy and global orientation: Britain still saw itself as a global power with strong ties to the Commonwealth and the United States. European integration seemed, to many in Britain, like a narrowing of its global reach.

- Economic self-sufficiency: Britain believed it could flourish economically without joining the European bloc, relying on its domestic industry, the Commonwealth trade network, and close ties with the U.S.

- Sovereignty concerns: Integration was seen as compromising national sovereignty. The supranational ambitions of the EEC clashed with Britain’s preference for intergovernmental cooperation.

As a result, Britain declined to join the ECSC and later chose not to sign the Treaty of Rome in 1957.

2. Change of Course: Britain Seeks Membership

Britain’s initial stance of detachment soon proved economically disadvantageous. As the EEC flourished and British industry lagged behind, there was a growing realization that being outside the Common Market had economic and political costs. Consequently, Britain applied for EEC membership in 1961, but its application was vetoed by French President Charles de Gaulle in both 1963 and 1967. De Gaulle viewed Britain as a Trojan horse for American influence and questioned its commitment to European integration.

Only after de Gaulle’s resignation in 1969 was Britain’s path cleared. Under Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath, Britain finally joined the EEC in 1973, alongside Ireland and Denmark. However, this accession did not mark an enthusiastic embrace of the European project. It was seen more as an economic necessity than a political commitment to unity.

3. Ongoing Ambivalence and Opt-Outs

Throughout its membership, Britain maintained a cautious and utilitarian approach to European integration. It consistently sought to limit the political ambitions of the EU and to safeguard its sovereignty. Several examples underscore this stance:

- 1975 Referendum: Just two years after joining, the Labour government of Harold Wilson held a referendum on continued EEC membership. Although 67% voted to remain, the very fact that a referendum was held highlighted the persistent divisions within British politics on Europe.

- Budget Rebate (1984): Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, a staunch critic of EU bureaucracy and budget allocations, successfully negotiated a rebate on Britain’s contributions to the EU budget, arguing that the UK was paying more than it received. Her famous demand, “I want my money back,” epitomized Britain’s transactional view of the EU.

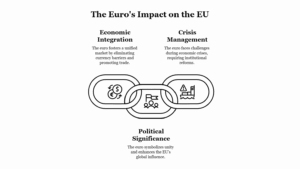

- Maastricht Treaty Opt-Outs (1992): Under Prime Minister John Major, Britain secured opt-outs from the Eurozone and the Social Chapter of the Maastricht Treaty. While the Treaty marked a major step toward political union in Europe, Britain resisted moves that would deepen integration.

- No to the Euro: Britain chose not to join the single currency (the Euro) when it was introduced in 1999, keeping the pound sterling instead. Successive British governments cited concerns over loss of monetary sovereignty and economic flexibility.

- Skepticism of the Schengen Agreement: Britain also opted out of the Schengen Zone, choosing to retain border controls. This again reflected fears of losing control over immigration and national security.

These examples indicate that Britain’s participation in the EU was often conditional and guarded. While other member states saw the EU as a step toward deeper political integration and even federalism, Britain largely viewed it as a free trade area and economic alliance.

4. Rise of Euroscepticism and the Brexit Vote

The 1990s and 2000s witnessed the rise of Euroscepticism in Britain, with growing sections of the political class and public opinion opposing further integration. The expansion of the EU, immigration concerns, and the perception of increasing EU control over domestic affairs fueled this sentiment. The emergence of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) under Nigel Farage further politicized anti-EU sentiment.

Amid growing pressure from within the Conservative Party and UKIP, Prime Minister David Cameron promised an in/out referendum on EU membership. In June 2016, 52% of British voters chose to leave the EU, leading to Brexit—the first departure of a country from the union.

Brexit was the culmination of decades of British ambivalence toward European integration. The vote reflected a deep-rooted belief among many Britons that European integration had gone too far, threatening national sovereignty, democratic control, and cultural identity.

Conclusion: A Reluctant European

Britain’s trajectory in the European integration process was shaped by a complex blend of history, identity, political culture, and economic pragmatism. Unlike founding members of the EU who viewed integration as a way to overcome historical animosities and build a common future, Britain viewed Europe through a pragmatic lens—as a marketplace rather than a shared political destiny.

From refusing to join early European institutions to seeking opt-outs, resisting deeper integration, and finally leaving the EU altogether, Britain’s role in European integration was consistently hesitant and transactional. Its reluctance stemmed not only from elite political decisions but also from a broader public ambivalence, fuelled by a sense of distinct national identity and a preference for sovereign governance over supranationalism.

In retrospect, Britain’s reluctant participation in European integration underscores the tension between national sovereignty and collective European unity—a tension that remains central to the future of the European project.

Leave a Reply