The European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) represents one of the most significant milestones in the European integration process. It aims to unify the economic and monetary policies of European Union (EU) member states through the adoption of a single currency and coordinated macroeconomic governance. The EMU is the culmination of decades of efforts to build a stable, integrated European economy, and its background is deeply rooted in both economic necessity and political ambition.

Historical Background

The idea of economic and monetary integration in Europe has origins that go back to the post-World War II period. In the aftermath of the war, European nations sought peace and prosperity through economic cooperation. The 1957 Treaty of Rome, which created the European Economic Community (EEC), laid the foundation for economic integration by establishing a common market and customs union. However, monetary integration remained limited.

The first significant attempt at monetary cooperation came with the Werner Report of 1970, which proposed a three-stage plan to achieve economic and monetary union over a decade. It envisioned fixed exchange rates and common economic policies. However, global economic shocks—especially the collapse of the Bretton Woods system and the 1973 oil crisis—derailed these ambitions. The European Monetary Snake (1972), an arrangement to maintain stable exchange rates among European currencies, also failed due to inflation and diverging economic conditions across member states.

Revival of Monetary Integration: The Delors Report

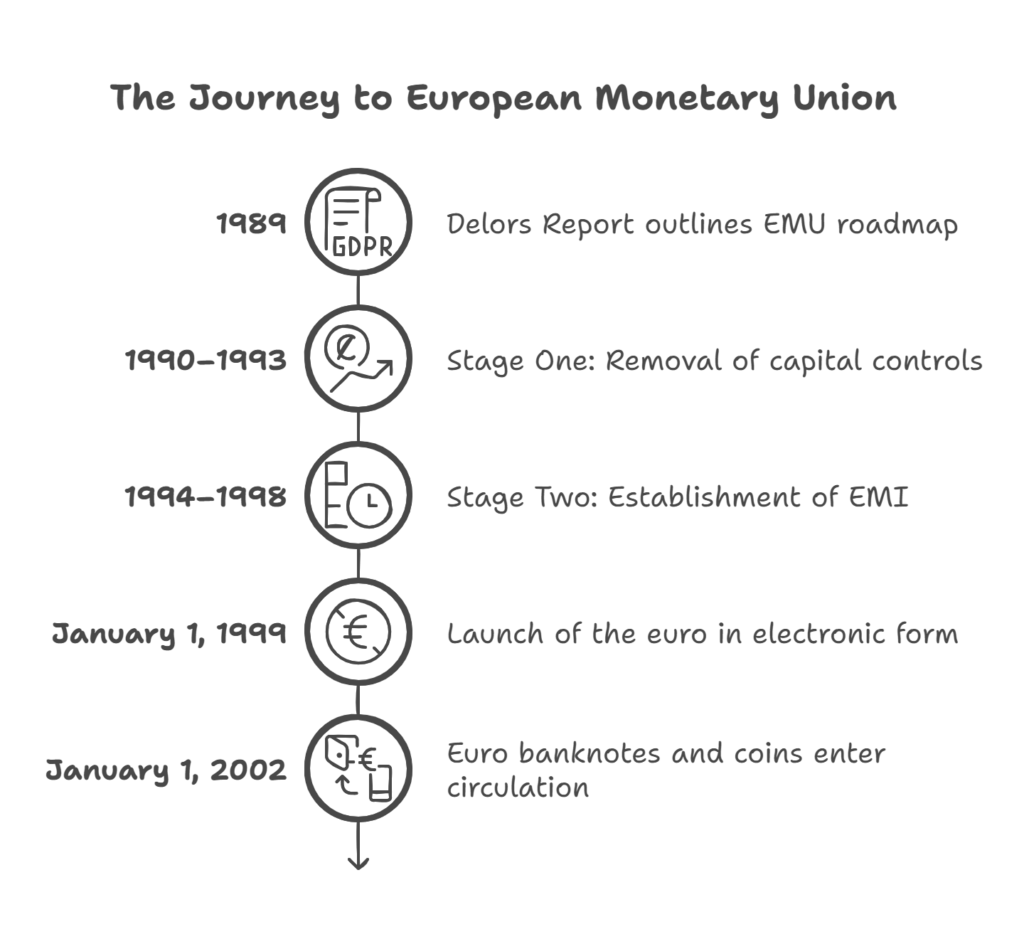

The idea of monetary union regained momentum in the 1980s, as economic globalization increased and the internal European market matured. The turning point came with the Delors Report (1989), named after European Commission President Jacques Delors. This report laid out a detailed three-stage roadmap for achieving economic and monetary union. It identified the necessity for central monetary authority, coordination of economic policies, and the irrevocable fixing of exchange rates.

Three Stages of the EMU

- Stage One (1990–1993): This phase involved the removal of capital controls, increased economic policy coordination, and enhanced cooperation among national central banks.

- Stage Two (1994–1998): The European Monetary Institute (EMI) was established as a precursor to the European Central Bank (ECB). Member states began to align their national policies to meet convergence criteria set out in the Maastricht Treaty.

- Stage Three (1999 onwards): On January 1, 1999, the euro was launched in electronic form for banking and financial transactions. On January 1, 2002, euro banknotes and coins entered circulation, replacing national currencies in participating countries. The European Central Bank (ECB) assumed full responsibility for monetary policy.

The Maastricht Treaty and Convergence Criteria

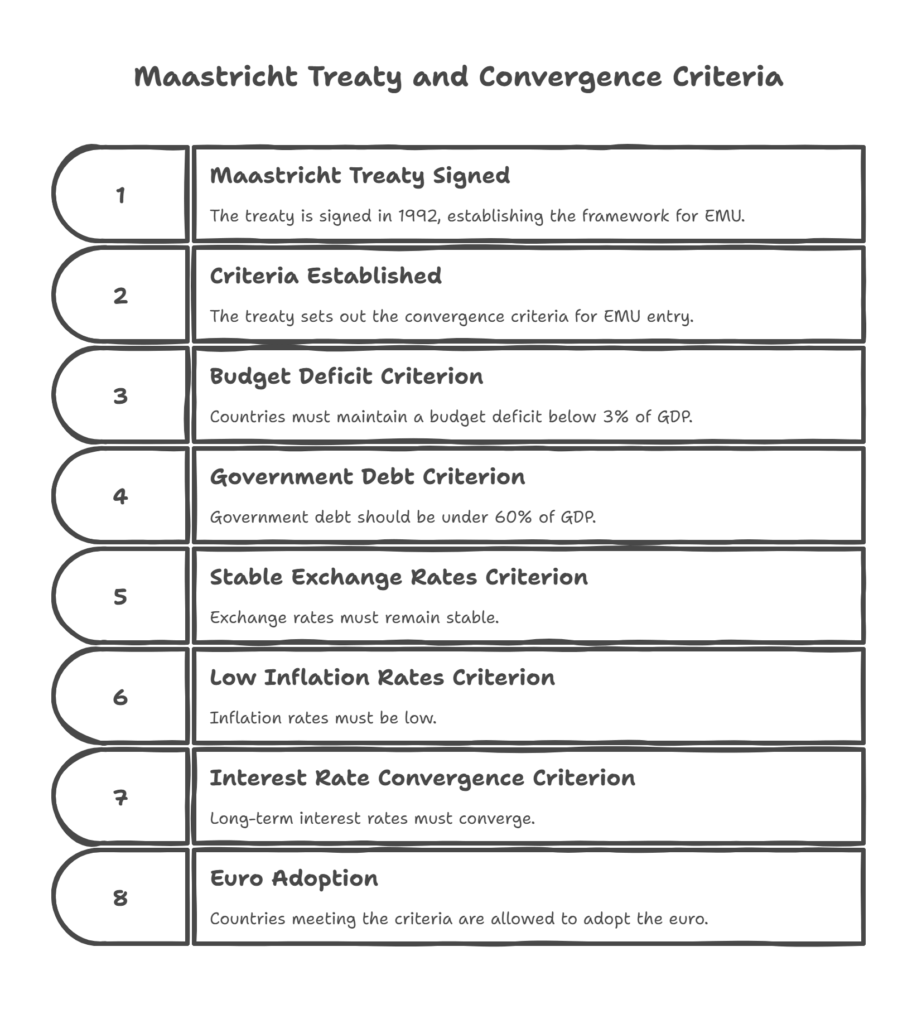

The legal and institutional framework for the EMU was provided by the Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty), signed in 1992. This treaty established the criteria for entry into the monetary union—commonly known as the Maastricht Convergence Criteria. These included:

- A budget deficit below 3% of GDP

- Government debt under 60% of GDP

- Stable exchange rates

- Low inflation rates

- Long-term interest rate convergence

Only countries that met these criteria were allowed to adopt the euro.

Economic and Political Motivations

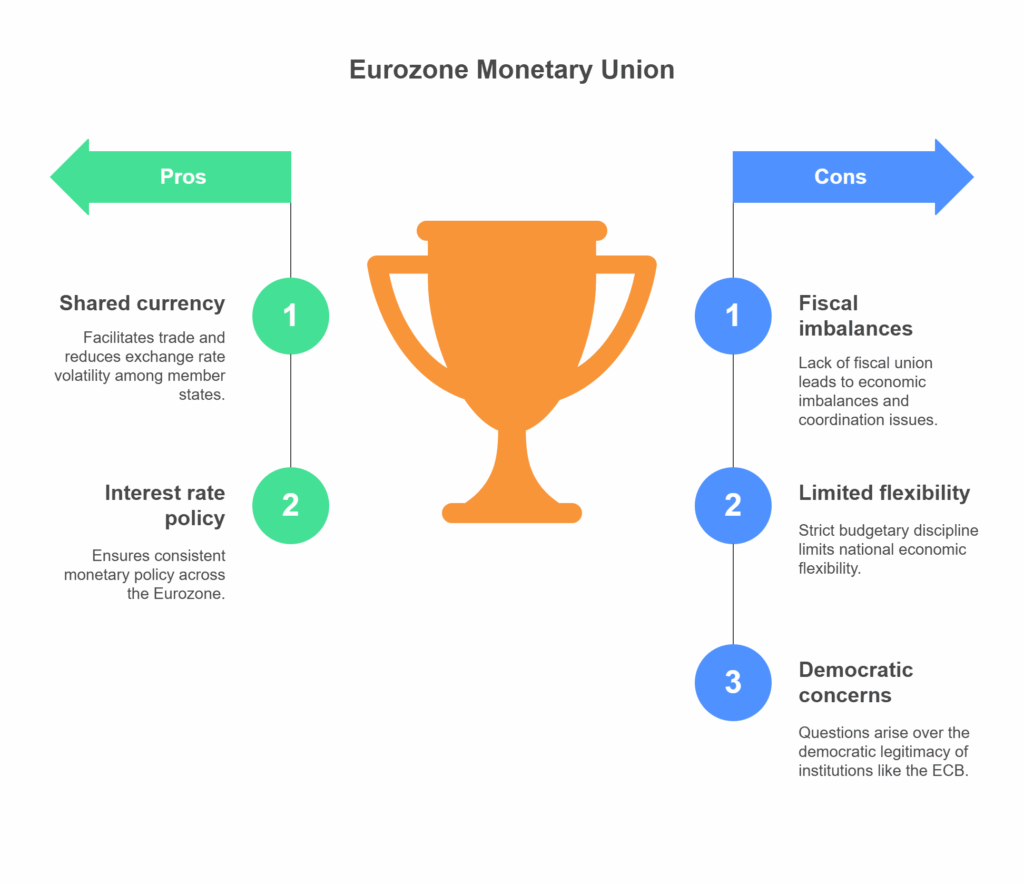

The EMU was not only an economic project but also a political one. Economically, the euro was expected to reduce transaction costs, eliminate exchange rate fluctuations, promote price transparency, and strengthen the internal market. Politically, it symbolized a deeper unity among EU member states and was seen as a stepping stone toward greater political integration and stability.

Challenges and Criticisms

Despite its successes, the EMU has faced several challenges. The Eurozone crisis (2009–2012), sparked by the Greek debt crisis, exposed the flaws in the monetary union—particularly the lack of fiscal union to complement monetary policy. While countries shared a currency and interest rate policy, they retained control over taxation and spending, leading to imbalances and coordination problems.

Critics argue that the EMU imposes strict budgetary discipline that limits national flexibility, especially during economic downturns. There is also debate over the democratic legitimacy and accountability of institutions like the ECB.

Conclusion

The European Economic and Monetary Union is the result of a long and complex journey toward deeper economic integration in Europe. It evolved through decades of trial, error, and political negotiation, driven by both economic logic and a vision of European unity. While it has brought notable benefits, such as increased trade and monetary stability, it also continues to face structural challenges that require ongoing reform and adaptation. The EMU remains a dynamic and evolving pillar of the European project.

Leave a Reply